Though the Border Patrol was established in 1924, and some militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border region occurred prior to recent decades, it has been in the years following the 9/11 catastrophe that the border has been subjected to unprecedented military escalations. When the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created in 2002, the agency formerly known as Immigration and Naturalization Services was moved from the Department of Justice to DHS, and immigration enforcement programs and policy emphasized a focus on anti-terrorism. Since then, militarization has been steadily increased and normalized at the U.S.-Mexico border and within border enforcement agencies.

By border militarization, we refer to the systematic intensification of the border’s security apparatus, transforming the area from a transnational frontier to a zone of permanent vigilance, enforcement, and violence. The border has become an imagined war zone, where the war on drugs, crime, and aliens are fought. Such arrangements make the border an area where the U.S. constitution has little to no value, a post-constitutional territory that expands across the country.

The outcome of border militarization has not been to deter migration, but instead to create more vulnerability.

This page provides an introduction to border militarization, and more detailed information about the issues mentioned here can be found on our other pages: Border Enforcement Accountability and Corporate Interests at the Border.

FUNDING OVERVIEW

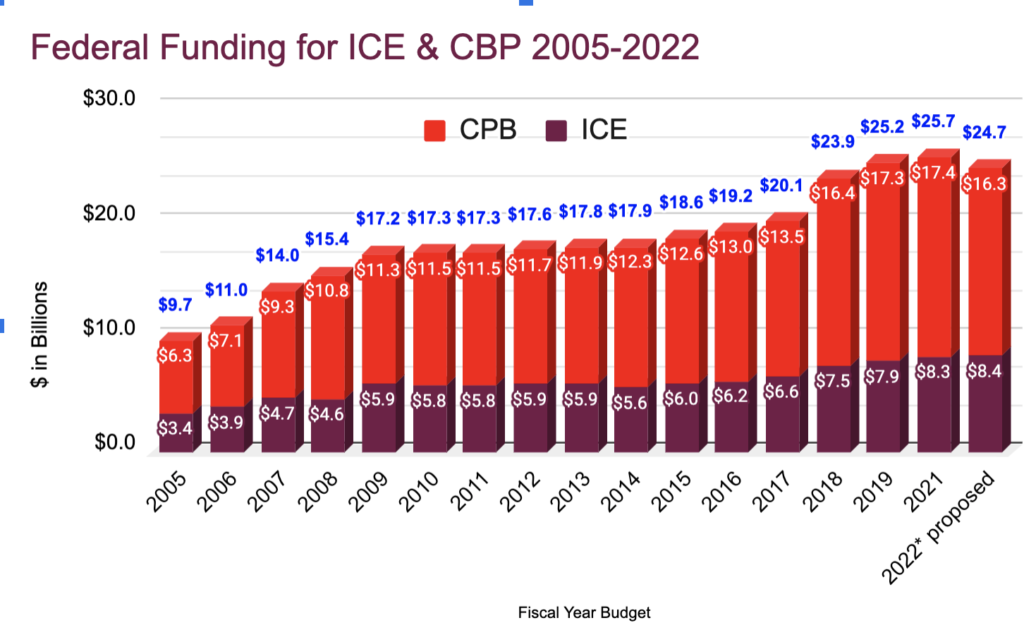

One of the clearest ways to identify the growth of militarization at the border is by looking at the colossal spike in funding for border security over the years. The funding for border enforcement agencies surpasses the funding of all other federal law-enforcement agencies (FBI, DEA, ATF, Secret Service and U.S. Marshals Service). The American Immigration Council estimates that $263 billion dollars have been spent on immigration enforcement since 1986.

This graph above depicts federal funding for ICE and CBP per year, from 2005 through the proposed 2022 budget (released May 2021) which is to be approved in fall 2021. NNIRR and allies in the immigrant rights movement are enraged with the Biden administration for keeping funding at the same level as during Trump years, breaking with a promise to bring relief to immigrant communities and decrease the funding for enforcement. Who benefits from these numbers? The many corporations with government contracts providing technology, security and military equipment, private prisons and more…

According to a 2013 Migration Policy Institute Report, “funding, technology, and personnel growth are the backbone of the transformations in immigration enforcement.” The majority of government funding for border securitization ends up going to security and technology corporations like Boeing Company, Raytheon, and Elbit Systems. Tellingly, after Trump was elected on a platform of border militarization and securitization, investment in many of corporations like these rose. In Border Patrol Nation, journalist Todd Miller describes this connection as a “brave new world of border control where the lines of separation between private industry and the U.S. government are increasingly blurred.” For more information, visit our page on corporate outsourcing of border militarization.

“MEN IN GREEN”: CUSTOMS AND BORDER PATROL AGENTS

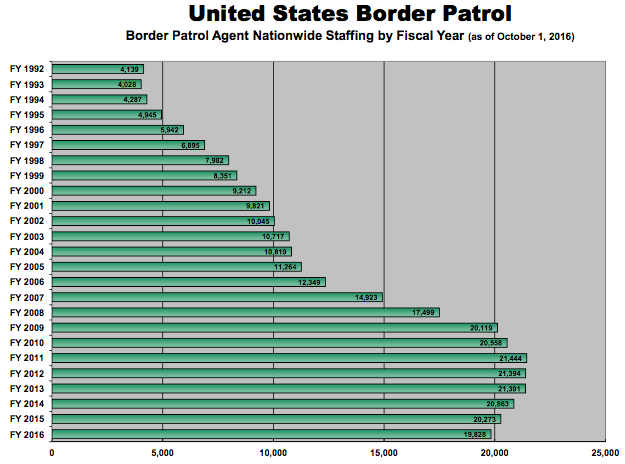

Calls for increased border security often include increasing the number of border patrol agents. Since the implementation of the 1994 Border Patrol Strategic Plan, the number of Border Patrol agents has grown nearly fivefold, from 4,287 to 19,282.

More “boots on the border”?: The argument that increasing the number of agents makes the border “safer” is not well supported. As the number of agents has increased, the number of people each agent apprehends has decreased, suggesting that there is little correlation between hiring more agents and apprehending more undocumented border crossers:

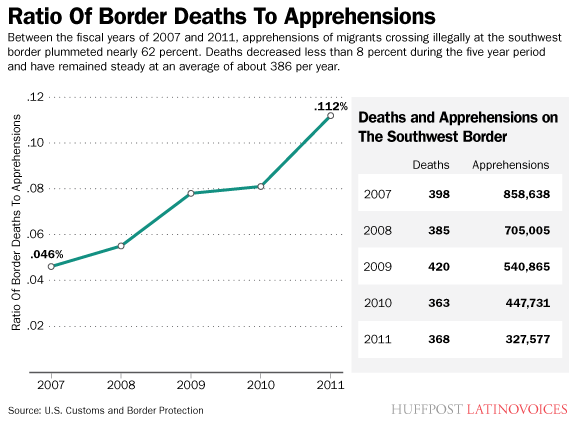

Instead, the primary consequences of more agents are their overwhelming presence in border communities, where they police the activities of residents and contribute to a militarized environment, and an increase in the number of migrants who die attempting to cross the border. As more agents patrol the border, migrant routes are pushed into more and more dangerous terrain.

Military-style operations and ideology: Border militarization includes not just increased tactics, technology, and strategy, but also rhetoric and ideology. The first sentence of the CBP mission statement reads, “The priority mission of the Border Patrol is preventing terrorists and terrorists weapons, including weapons of mass destruction, from entering the United States.” This contradicts with the reality of human rights needs at the border, as agents are trained to treat the people they encounter as military combatants. The militarized nature of border enforcement agencies is evident in the profile of many of their agents as well. Customs and Border Patrol practices a hiring preference for veterans, and according to their website, over a third of CBP officers have served in the military.

Veterans undergo an expedited hiring process. Despite the agency’s history of corruption, Republican Congress members have proposed legislation to expedite the process further by making veterans, as well as law enforcement officers, exempt from the polygraph test.

The University of Arizona’s 2013 Migrant Border Crossing Study compiled information from over a thousand interviews with deportees about their experiences with violence at the border. They provide evidence of Migrant Mistreatment While in Custody as well as their Possessions Take and Not Returned.

U.S. border and immigration enforcement agents are also contributing to militarization abroad, and this article by Todd Miller in The Nation, “Wait, What are US Border Patrol Agents Doing in the Dominican Republic?,” shows how international training programs push “homeland security” beyond our geographic borders.

CBP’s history of abuse: The rapid expansion of the Border Patrol in the last decade has created problems with training and screening. Coupled with the military-style operations and ideology, this has led to an agency that is rife with abuse towards undocumented people and residents. The Southern Border Communities Coalition identifies “a deeply ingrained culture of violence” in the Border Patrol agency that is “out of control and operates with impunity.” The problem has not been addressed within the Department of Homeland Security, and it is difficult for the public to gain access to information about how allegations of abuse are handled.

To learn more about issues of abuse, corruption, and impunity in border enforcement agencies, visit our page on Border Enforcement Accountability.

BORDER MILITARIZATION PROGRAMS AND POLICIES

In 1994 (the same year that NAFTA was signed), the now-nonexistent Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) introduced the first formal border control strategy. This was the beginning of what is known as “prevention through deterrence,” which was manifested in local border operations like Operation Hold the Line (El Paso, TX), Operation Gatekeeper (San Diego, CA), and Operation Safeguard (Tucson, AZ). In Texas, the state-wide Operation Rio Grande was later created. Seeking to prevent unauthorized immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border through so-called “deterrence” strategies, these initiatives claimed to reduce repeated unauthorized entry by deploying many more agents at the border, installing electronic surveillance at the border, and erecting border infrastructure, such as fences and stadium lighting, to deter illegal entry. The prevention-through-deterrence strategy succeeded in forcing people to reroute into more dangerous terrain, but did not reduce the number of people attempting to cross due to the need to escape violence, economic hardship, or family separation. This change also created a growth in the market for human smugglers with knowledge of the terrain.

Starting in 2005, with the post-9/11 national security logic, the border’s militarization policies and practices exploded. The Secure Border Initiative (SBI) tremendously expanded technological and infrastructural capabilities of border agencies; sensors, radars and drones became commonplace. That same year saw the beginning of Operation Streamline, a program first initiated in the Texan Del Rio sector and later expanded to the rest of the border. Heavily criticized by activists, Streamline factually criminalizes and prosecutes undocumented border crossers through mass hearings and fast-track prosecutions, detaining individuals for months with unfair proceedings.

2006 then saw the congressional approval of the Secure Fence Act, a multi-billion dollar bill that called for the construction of the border’s fence. This move has split binational communities, interrupted historical seasonal migration, and transformed the U.S. border into a physical warzone. This year also saw the end of “catch and release,” now detaining all non-Mexican immigrants until hearings took place.

In 2008, the Secure Communities program began. Under Secure Communities, local enforcement agencies run fingerprints for detainees through FBI and DHS databases. If there is a match between the two (that is, the individual has a criminal conviction and an issue with their immigration history), the information is cross-referenced by ICE with other databases to assess if the person is removable from the U.S. If a case is found,ICE can then request the local enforcement agency to detain the person for immigration proceedings. As of 2011, the program is active nationally, with local agencies determining whether they will cooperate with ICE’s requests. A highly racialized program that has torn families apart for minor convictions, Secure Communities has expanded militarization to police forces in communities along the border. The warzone has invaded neighborhoods that can no longer trust criminal enforcement.

Secure Communities was subject to several legal challenges and in November 2014, was replaced with the Priority Enforcement Program, or PEP. Immigration advocates argued that PEP was little different from Secure Communities. Most recently, President Donald Trump, in an executive order on January 25, 2017, announced that the PEP program would be ended and that Secure Communities would be revived.

In 2012, the framework of prevention through deterrence evolved into a 2012-16 strategy for enforcement, articulated through the Consequence Delivery System (CDS). CDS is made up of border and immigration enforcement programs which seek to actively punish, incarcerate, and criminalize unauthorized immigrants and therefore prevent reentry through a “whole-of-government” approach. Under this logic, apprehended immigrants are to be further criminalized and punished for their attempts to cross the border, no longer granting voluntary return. Immigrants prosecuted for illegal entry and reentry gain criminal records and serve time prior to deportation, feeding the private prison industry. CDS also recommends more expedited removals, barring hearings or requests for political asylum to immigrants.

The Trump administration’s first actions on immigration included expanding the use of “consequences,” such as directing prosecutors to pursue criminal charges whenever possible, raising mandatory minimum sentencing, and expanding the use of expedited removal. After the first 6 months of 2017, the Migration Policy Institute wrote a summary of the “Sea Change in Immigration Enforcement” from the Trump administration.

EFFECTS OF BORDER MILITARIZATION

The consequences of the militarized U.S.-Mexico border include ciolence, community fractures, unreported abuses, and death.

Indefensible: A Decade of Mass Incarceration of Migrants Prosecuted for Corssing the Border (July 2016). From Garssroots Leadership and Justice Strategies; an indictment of Operation Streamline and the criminalization of undocumented, prosecuted for entry and re-entry violations. An argument for an intersectional approach to migration and criminal justice.

On the Front Lines: Border Security, Migration, and Humanitarian Concerns in South Texas (February 2015). This report from the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) provides an overview of the policies and consequences of U.S. border policies in conflict with the increased flow of migrants across the border into South Texas. The report includes policy recommendations concerning due process, deportations, border security, and migrant deaths.

Border Network for Human Rights organizes an annual abuse documentation campaign to shine a light on the negative consequences of border militarization for borderlands communities. The 2013 preliminary report can be found here, and the full list of reports released by the BNHR can be accessed here. People Helping People of Arivaca, Arizona has also compiled resources on the presence of Border Patrol in their community. Watch a video of community members testifying on this subject in 2015.

A 2013 article by Jennifer Correa, “After 9/11 Everything Changed”: Re-Formations of State Violence in Everyday Life on the US–Mexico Border, documents the effects of border militarization in the lives of residents of Cameron County, Texas. Premised on the racialized fears rationalized by the ‘war on terror,’ the author argues that American communities and foreigners alike must go through the state violence expressed by this militarization.

Mother Jones has an in-depth report that narrates how the border zone has become post-constitutional warzone where constitutional rights no longer matter. This is a direct effect of indiscriminate border militarization, and U.S. citizenship is not a defense against it.